History

Under Construction

|

HistoryUnder Construction |

|

Founded, presumably, some 700-800 years ago (the exact date is uncertain), Berlin's golden age began at the end of the 19th century, when, in 1871, it became the capital of the newly unified German Empire. In the same year, Germany won the Franco-Prussian war, and a large part of the reparations paid by France were invested in Berlin.

As the city expanded and industrialized, an organized urban workers' movement gained more and more ground.

In 1914, at the beginning of the First World War, the emperor called on Germans to unite. In an allusion to the divided parliament, he stood on the balcony of his Berlin palace and proclaimed, "I know no parties, only Germans."

|

Kaiser Wilhelm II. addresses his subjects in 1914, from the City Palace in Berlin. |

During the war, there was some degree of unity, more or less. After the war,

however, all the conflicts that had existed previously came to a head.

In 1918, at the end of World War One, facing defeat, the German emperor fled

to Holland. As the emperor fled, socialist leader Karl

Liebknecht (who, with Rosa Luxemburg, headed the Spartakus-Bund) stood on

the same balcony from which, four years earlier, the emperor had called for

German unity. Liebknecht now called

forth the German Socialist Republic. However, on the same day - November

9th, consistently an important date in German history - Philip Scheidemann

called forth the parliamentary republic. After several riots and insurrections,

the parliamentary republic carried the day, but its victory came at the expense

of the alienation of much of Berlin's working class, many of whom supported

the more radical brand of socialism espoused by the Communist Party.

The decades following World War One were marked by the city's growth and also a growing gulf between leisure-class urbanites and the industrial urban working class. Berlin became known both as a city of libertines and a hotbed of socialist radicalism (not for nothing was it sometimes referred to as "Rotes Berlin." Logically enough, support for the Nazis was lower here than anywhere else in Germany - though it still could not be considered low in any absolute sense. In the 1933 elections that brought Hitler to power, fully one quarter of Berlin's population voted for the vehemently (and often violently) anti-Nazi German Communist Party (twice the national average), while the percentage of Nazi voters, at 35%, was 10% lower than the national average. Even before 1945, Berlin was a city deeply divided, and anecdotal evidence seems to show that Berlin was both the Nazi capital and the capital of anti-Nazi resistance.

After the Nazis consolidated their power, they wanted to place their architectural stamp on Berlin, a city with which they had a somewhat antagonistic relationship. "Ihr werdet Berlin nicht wiedererkennen," Goebbels said of plans to remodel the capital - "You will not recognize Berlin."

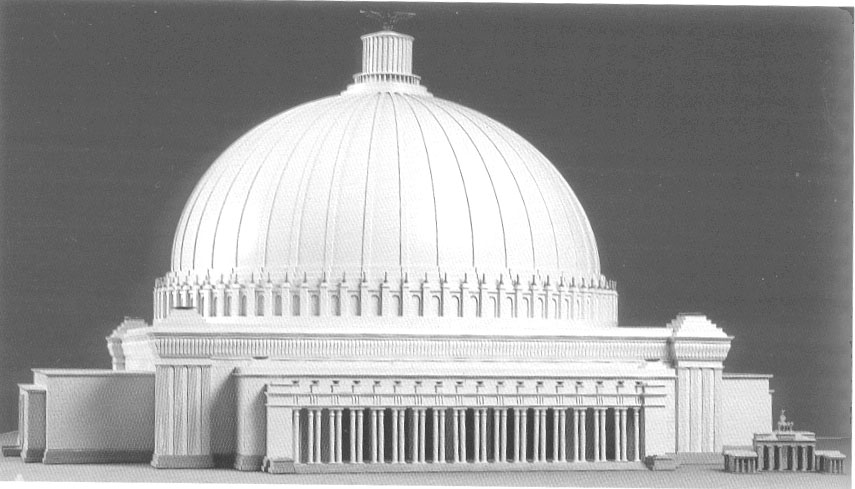

|

Albert Speer's planned capitol building. For a sense of scale, note the Brandenburg Gate, at the lower right. |

In spite of the fact that Albert Speer's truly megalomaniacal plan to remodel the entire city and rename it Germania was never instituted, a number of individual buildings were completed, and you can still see some fascist architecture in Berlin today, for instance, at Tempelhof Airport. Many of the debates about what is to be built now in Berlin center around how much contemporary conservative architecture echoes fascist themes. The Nazi headquarters were in Berlin, now the location of a museum and memorial site, the Topography of Terror, whose fate is uncertain.

The Holocaust, one of the central traumas of the 20th century, left its traces

on Berlin. Before the war, about 60,000 Jews lived in Berlin; after 1945, that

number had dwindled. The synagogue in the Oranienburger Straße escaped

the desctruction of Kristallnacht through the intervention of a courageous fireman,

though it was later desecrated, parts of it were destroyed, and it was used

to store Nazi weapons. The Prenzlauer Berg synagogue building survived only

because it stood so close to neighboring buildings that residents were afraid

that if they burned it down, their houses would burn as well.

The systematic destruction of the Jews was planned at the Wannsee Conference,

in a villa on Berlin's outskirts; the Sachsenhausen concentration camp is an

hour from the city center on the train. Debates about whether and how to memorialize

this past have been a fixture in postwar Berlin, from 1945 through the present

day.

During World War Two, large parts of the city were destroyed - about 600,000

housing units - and interestingly enough, it was working-class areas like Wedding

and Kreuzberg that sustained the heaviest damage, while richer areas like Charlottenburg

and Wannsee went relatively undamaged.

After the end of WWII, the city was split into four different administrative

parts, and in 1949, when the two German states were founded, were more or less

merged into two, although Berlin was still officially divided into French, American,

British and Soviet zones until 1991.

In the years between 1945 and 1989, Berlin became perhaps the primary showcase

of the Cold War. The determination of both the Eastern and Western blocs to

hold onto Berlin was demonstrated early on during the Berlin Blockade of 1948-49,

when the Soviet Union closed land access to Berlin and the Western "Raisin

Bombers" flew food and fuel to the blockaded city for almost a year. Both

the West and East German governments subsidized Berlin far more heavily than

any other city, well aware of the city's symbolic value. In spite of the efforts

at rebuilding, ruins marked the landscape of both Berlins for decades, and even

today you will see walls filled with bulletholes. Two prominent buildings in

the West remain purposefully in ruins.

In the East, the royal palace, heavily damaged by bombs, was destroyed in 1950.

In its place a glass-and-stone Palace of the Republic was built, which housed

the East German parliament as well as restaurants and bowling alleys for use

by common citizens. Only one part of the royal palace was saved, as part of

the East German effort to replace many of the imperial markers with socialist

ones - the balcony from which Liebknecht called forth the socialist republic.

Meanwhile, particularly in the 1950s, so-called Plattenbauten began to dominate

the residential landscape - strapped for cash, the government built low-quality

but high-residency prefab apartment buildings. In 1953, the first and, for decades,

last major anti-government protest occurred, as thousands of workers took to

the streets to protest poor working conditions - a major embarrassment to the

socialist state. The protests ended violently; exact numbers have never been

given, but even the official figures listed 21 dead and 187 injured, not to

mention about 13,000 imprisoned.

West Berlin, meanwhile, benefited from the "Wirtschaftswunder," the

upswing in the economy in the 1950s, a decade of rebuilding and prosperity.

The West German capital was moved to Bonn for the next 50 years, and in the

wake of the Blockade, Berlin was considered a risky investment. It was subsidized

heavily by the government, which offered generous incentives for people to move

to Berlin. With the institution of mandatory military service in West Germany

in 1956, Berlin also became a haven for peaceniks, as Berlin residents were

exempt from this service.

In August 1961, the Wall was erected, in large part as a response to growing

discontent within the GDR and the increasing flight of East Germans to the West.

It is no exaggeration to say that this event shocked much of the world, not

only for its audacity but also for its unexpectedness; the Wall was erected

almost overnight. It too became a heavily symbolic location for conflict between

the East and the West. Few believed the East German government's claims that

the Wall was built to protect the GDR from the fascist West, particularly given

the number of escapes and attempted escapes by Easterners. John F Kennedy made

history in his 1963 "I am a Berliner"

speech.

Particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, the area around the Wall became a favorite

location of leftist protestors. The Wall had been built in the Soviet sector,

and the borders of the Soviet sector extended about five feet beyond the Wall.

Practically, this area was a no-man's land, where Western police had no jurisdiction.

Occasionally, protesters actually jumped over the Wall into the East, where

they were generally greeted cordially, given coffee, and escorted back to the

border (the East seeing this, understandably, as a fine chance for propaganda).

The collapse of the GDR was not only an ideological challenge for the German

left, but a practical challenge for the radical movements in Berlin.

The graffiti on the Western side of the Wall was also a vast blank canvas for

art and ideological critique.

In the 1960s and 1970s, West Berlin was once again known as the leftist city.

Years of anti-military migration contributed to the formation of a substantial,

radically leftist student movement. Protesters were habitually met with the

phrase, "Geh doch rüber!" - "Just go over there!" -

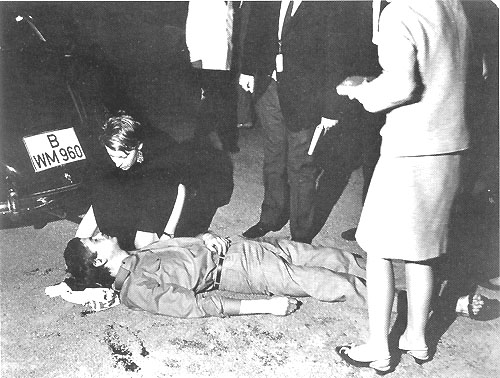

and police were often brutal, even firing on crowds. (Benno Ohnesorg's shooting

in 1967 in Berlin had much the same impact as Kent State did in this country.)

|

Benno Ohnesorg, shot in the back by police at a protest against the Shah of Iran in 1967 |

The late 1970s and 1980s were relatively quiescent; as the Western and Eastern

blocs slowly moved toward détente, Berlin's symbolism was more uncomfortable

for both sides. This remained the case until 1988-9, when months-long anti-government

protests in East Berlin resulted in the Wall not falling but being surmounted.

The pictures of Berliners celebrating atop the Wall in November 1989 are perhaps

the most prominent images of the eventual fall of the Eastern Bloc.

Berlin is also a city of immigrants, and an ideological battle around issues

of immigration is being fought at all levels. The city's population is over

10% "foreign," in some areas so-called foreigners make up almost half

the population. Still, many politicians refuse to see Germany as a site for

immigration; nevertheless, the city's enormous construction boom lives off the

work of illegally immigrated laborers. Immigrants come primarily from Turkey

and the former Eastern Bloc, but there are substantial minorities of African

and Latin American immigrants as well. (European Union citizens aren't usually

considered immigrants.]

Now, Berlin is again the site of ideological and architectural battles. Constant

debates surround the issue of how the New Germany should be represented. Major

new building has taken place, both privately and publicly. I left town for three

weeks once and when I returned, an old building on the corner by my subway stop

had been replaced by a new hotel. There was nearly a decade of debate on whether

a Holocaust memorial should be built and if so, how and where; a similarly contentious

debate surrounded the Palast of the Republic and whether it should be destroyed

and if so, whether the old Royal Palast should be rebuilt in its place. Both

of these questions, while they have received several different parliamentary

answers, do not seem to have been finally settled. Christo's Wrapped Reichstag

project (June 1995) foregrounded a lot of these questions, enclosing the old

parliament in thousands of meters of gauze while the national parliament in

Bonn decided what to do with it. Many of the battles are also fought over street

names. Street names in Germany, and especially in Berlin, are extremely political.

The West, for example, named one of its major streets "Street of the 16.

June," the date of the workers' uprising in Berlin, while the East named

its streets after communist leaders like Lenin and Ho Chi Minh. City plans from

the different eras of Berlin are fascinating, as streets go through continual

renamings - Kaiser-Wilhelm-Platz to Schloßplatz to Marx-Engels-Platz,

and now many of the socialist street names are being reconsidered - often to

severe opposition.

Berlin is in many ways a physical representation of many of the 20th century's major ideologies and events, events that often called into question precisely those ideas of modernity that were developed in the 19th century. It is also a site of constant struggle, from 1871 to the present day, to define what a nation is, and what the German nation in particular is and is not. Particularly now that most of the government has been moved to Berlin, it is once again a heavily contested site. The new office of the chancellor was built, many critics say, with a fear of the people in mind, and this antagonistic relationship between the people and the government is also one of the markers of Berlin.